Toulmin

Toulmin's system suggests a middle ground might hold between the hyper-rationalism of analytical philosophy (and the science establishment) and the absurdity and anti-rationalism of postmodernism and marxist aesthetics (tho' we here at Contingencies once in a great while peruse the "textual idealism" of Derrida's Of Grammatology with amusement).

Toulmin's emphasis on practical argument also seems somewhat pragmatist: there are, of course, advantages and disadvantages to pragmatism--the "cash value of Truth" model, as Wm James called it---whether in terms of philosophy or politics. Toulmin, however, understands the problems --and unworkability--of the academic logician's worship of necessity and formal validity; one might think of Toulmin's approach as applied inductive logic, analogous to applied engineering mathematics (and contrasted to the "Theory of the Calculus" posited by those holymen Leibniz and Newton). Though it's unlikely Toulmin-fever will catch on soon, Toulmin offers a fairly comprehensible and sensible approach to communication--one that might conceivably be implemented on blogs, for example, if not the....San Phrancisco Cthulhucle.

In "The Uses of Argument" (1958), Toulmin offered a schema featuring six components for analyzing practical arguments:

1. Claim: conclusions whose plausibility or trustworthiness or "merit" must be established (note the avoidance of the absolute category of "Truth"). For example, if a person tries to convince someone that poverty leads to crime, the claim would be “Poverty leads to crime.” Similar to a conclusion (in a modus ponens argument), or hypothesis (in terms of trad. phil of sci.)

2. Data: the facts appealed to as a foundation or ground for the claim. For example, the person can (and should) support his claim with data, statistics, and any other evidence showing significantly higher rates of crime in poor areas (higher than in middle or upper class areas) supporting his claim “Poverty leads to crime (or poverty has a causal relation to crime).” (so the statement would be, "crime rates are higher in poor areas than in middle or upper class areas: in effect, the minor premise in a modus ponens). Data obviously entails probability and statistical issues, such as sampling (perhaps "confidence intervals" should be attached to the data-statements).

3. Warrant: a statement which justifies the "movement" from the data to the claim (a warrant is similar to a major premise/conditional statement, in modus ponens). In order to move from the data established in 2---"there are higher rates of crime in poor areas than in middle or upper class areas"---there needs to be a warrant bridging the gap between the data and claim, and supporting his claim “Poverty leads to crime": "Since poor areas have higher crime rates (thando middle class or upper class areas), poverty has a causal relation to crime." Note again this is not "necessary" in a tautological or mathematical sense. The warrant itself generally is an inductive generalization (as with most generalizations of "social science"), and involves probability and statistical issues, such as sampling (a point which Toulmin may overlook--perhaps "confidence intervals" should be attached to the warrant as well).

4. Backing: the Wiki on Toulmin refers to these as "credentials designed to certify the statement expressed in the warrant"; but it is really an evidentiary question. If the warrant seems overly conjectural, incredible, or merely plausible (instead of "nearly always the case"), the arguer must introduce backing for the warrant. Not all poor people are criminals, and not all criminals come from poverty. IN many practical arguments (where people might grant a warrant/premise) this might not be a problem, but at the level of economics or sociology or journalism it could be. Nonetheless, the warrant-construction is generally not too difficult--no more difficult than say an economist suggesting the historical effects of lower interest rates on consumer spending and the economy at large (which is to say, if most economic or sociological generalizations mean anything, then Toulmin's warrant model can work).

5. Rebuttal: these are statements recognizing possible exceptions to the claim. An obvious one would be that some poor people are hard-working, and are not criminals. And there might be other factors causing crime, even among the poor--mental health issues, education, or gangs. The rebuttal, we suggest, may simply be a recognition that the claim depends on an "existence generalization" (some, or sometimes, or "often") rather than a universal (all): "poverty is one causal factor of criminal behavior, but not the only one." So the arguer must support his claim--and possibly the warrant--with additional evidence which would overcome the rebuttal. This could be difficult, but overcoming the rebuttal strengthens the argument.

6. Qualifier: words or phrases which express the speaker’s degree of emphasis or certainty concerning the claim (thus could be part of the rebuttal, really). Such words or phrases include “possible,” “probably,” “impossible,” “certainly,” “presumably,” “as far as the evidence goes,” or “necessarily.” The claim “Poverty definitely leads to crime” has more force than does the claim “Poverty sometimes may result in crime.”

The first three components---“claim,” “data,” and “warrant”-- are considered to be the essential components of practical arguments (as are the two premises and conclusion in modus ponens), while the second three-- “qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”--- are not always needed in arguments.

In terms of modus ponens, Toulmin's schema looks something like this:

1st premise/Warrant: "If poor areas have higher crime rates (than do middle class or upper class areas), poverty has a causal relation to crime." (Backing may be needed here--and since the claim is contained in the consequent, any rebuttals would be dealt with at this stage as well)

2nd premise/Data: "poor areas do have higher crime rates (than middle class or upper class areas). (Grounds/foundation/evidence may be needed here) . Note that this is the antecedent to the conditional in 1st premise.

Conclusion/Claim: “Poverty leads to crime.”

It might be noted Toulmin's argument form is valid when put in form of modus ponens--though Toulmin most likely wanted to avoid the problems of inductive conditionals with his system). If warrant/1st premise is likely (strongly probable), the argument is cogent as any good inductive argument is--not "sound" as with modus ponens (at least one with necessarily true 1st and 2nd premises), but cogent.

Friday, January 25, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Custom Search

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(146)

-

▼

January

(24)

- No secret handshakes, II (BR's version)ψ(ιx(φx)) ≔...

- No Secret Handshakes, IHistory: Fundamental Condit...

- "On The Campaign Trail With Dennis Kucinich" (from...

- "Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft, mag zusehn, dass er ni...

- ToulminToulmin's system suggests a middle ground m...

- Clint-o-cratsThe case against Billary (Hitchens):"...

- Crepsecule with Alex S.Ah yeahh homie

- Reverend Obama, reduxYou need additional evidence ...

- Herren- und Sklavenmoral"Herrenmoral sei die Haltu...

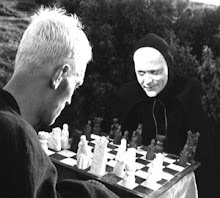

- Robert James Fischer, RIP"Marx was a very keen che...

- The Huckabilly Constitution The latest fundie-poli...

- Toastmasters from Hell (How not to write, continue...

- Reverend Obama, continued. Consider the connotatio...

- WHOA.

- Bubbanius on Modern Pedagogy (how not to write, co...

- A place you'll nevah Be

- Reverend Obama, cont. Here's a quote from a front-...

- Hysteria, Inc.William F. Buckley........on yahoo? ...

- Menckenism"Whenever 'A' attempts by law to impose ...

- Scryabinopolis

- Lancet Report lies (McMendacity II) Perhaps some h...

- McMendacityQuote: "a 95% white state just voiced t...

- Write-in

- Reverend ObamaBarack Obama has, over the last few ...

-

▼

January

(24)

1 comment:

I liked your point on cogent vs. sound!

Post a Comment